St Pega’s wall paintings and why we need to save them

The Significance of St Pega’s Wall-paintings and why we need to save them

By Dr Avril Lumley Prior (posted by David Hankins)

The Church and its wall-paintings

The present building was erected in 1014/15 as the ‘new minster at Pegecyrcan [Peakirk]’. In 1016, it received grants of land from King Edmund Ironside for the redemption of his soul, his wife, Ealdgyth’s, and that of her late husband, Sigeferth, the church’s founder. Due to its royal status, the church probably was completely covered with decorations, which were overpainted when they became shabby or unfashionable. Indeed, these murals were the illiterate parishioners’ illustrated Bible and were used as a teaching-aid by generations of parish priests. They were limewashed over during the reign of Edward VI (1547-53), who regarded religious imagery as idolatrous.

Why do we need to restore them?

In 1843/4, the archaeologist, Edmund Artis, reported the discovery of fourteenth-century wall-paintings at St Pega’s during structural repairs to the north-aisle wall. They were exposed by expert, Edward Clive Rouse, in 1950/1. Unfortunately, Rouse coated the paintings with beeswax as a preservative, a treatment that was already being frowned upon because it had a darkening effect, trapped moisture and salts, attracted dust and ultimately caused the plaster to flake. The wax was partially removed and some (though not all) of the paintings were stabilised by The Eve Baker Trust in the 1970s. The causes of the continued deterioration of the untreated paintings by seepage of water and fluctuating background temperatures were successfully addressed, in the 1990s. Nevertheless, conservator, Tobit Curteis, recommends that the plaster and pigments are stabilised, the wax and resin coatings reduced, superficial dirt is removed and that the paintings are repaired where possible. Without this work, they will deteriorate and, eventually, a significant amount of Peakirk’s – and also England’s – heritage will be lost.

What makes our wall paintings so special?

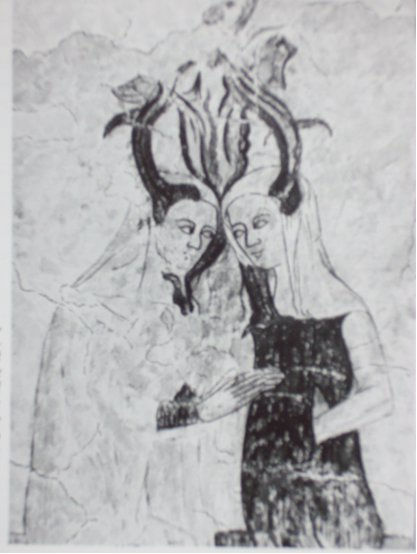

Art historians and conservators agree that the fourteenth-century Peakirk paintings are ‘of considerable importance’. The surviving excerpts from Christ’s Passion Cycle, St Christopher and the two moralities [moral tales] are exceptional for their quality and their artists’ meticulous attention to detail. Rouse describes the Crucifixion scene as ‘one of the finest examples of this subject’. Our St Christopher (a favourite in medieval churches) is particularly unusual. Kneeling at his feet is the fast-fading sponsor of the work, whilst the accompanying mermaid (with comb and mirror) recorded by Rouse, now has vanished. Above the North Door, there is an unusual version of ‘A Warning to Gossips’, depicting two women in medieval garb being encouraged in their pursuit by a devil pressing their heads together, untouched by conservators since 1950/1. To their east, is a second allegory of the wax-covered Three Living and Two Dead. (The third skeleton was destroyed by a layer of Victorian plaster.) Nevertheless, the scene is unique because of its gruesomely-realistic portrayal of death and corruption, a reminder in the years after the Great Plague of 1348/9 that death may strike at any moment.

Dear Madam or Sir,

May I kindly inquire if St. Pega’s Church will be open tomorrow (4th January)?

Many thanks for your help in advance.

Sabine

Hello Sabine. I’m sorry if no-one has got back to you before now. I’m pleased to confirm that the church is open every day(usually 10.00 – 4.00 minimum).

Did you get to visit?